In the AFM, there is a performance chart to determine actual landing distance for flaps 45. The chart considers items such as weight, altitude, head/tail wind and dry vs wet. What it doesn't consider however is thrust reverse. In fact, no where, in any manual that I can access, is thrust reverse mentioned for the flaps 45, dry runway case.

The chart I am referring to is found in the 'Landing Performance' section of the CRJ700 AFM and claims at 0' MSL, on a no wind, standard day, a 67,000lb (MLW) CRJ700 can come to complete stop with the nose wheel 3025ft from the threshold of the runway.

The landing technique outlined in the FCOM Vol. 2 indicates that Mitsubishi expects you to use full reverse thrust from nose contact to 90kts and returned to idle by 60kts.

The MEL for inoperative thrust reverse offers no performance penalty or adjustment.

The performance certification requirements 14 CFR 25.125(c)(3) specify that stopping means other than wheel brakes may be used if they are proved to be safe and reliable and consistent results can be expected in service.

I am going to assume Bombardier didn't think proving thrust reverser reliability was worth the trouble and just certified the aircraft and it's performance charts using wheel brakes alone. It simplifies the MEL/dispatch planning, and thrust reverse usage in the normal landing procedure is included as a bonus.

They do provide data with and without thrust reverse credit for the contaminated runway set of data. I assume there must be some exclusion to the 'proved to be safe and reliable with consistent results' clause above for the contaminated set of data, but I couldn't find it.

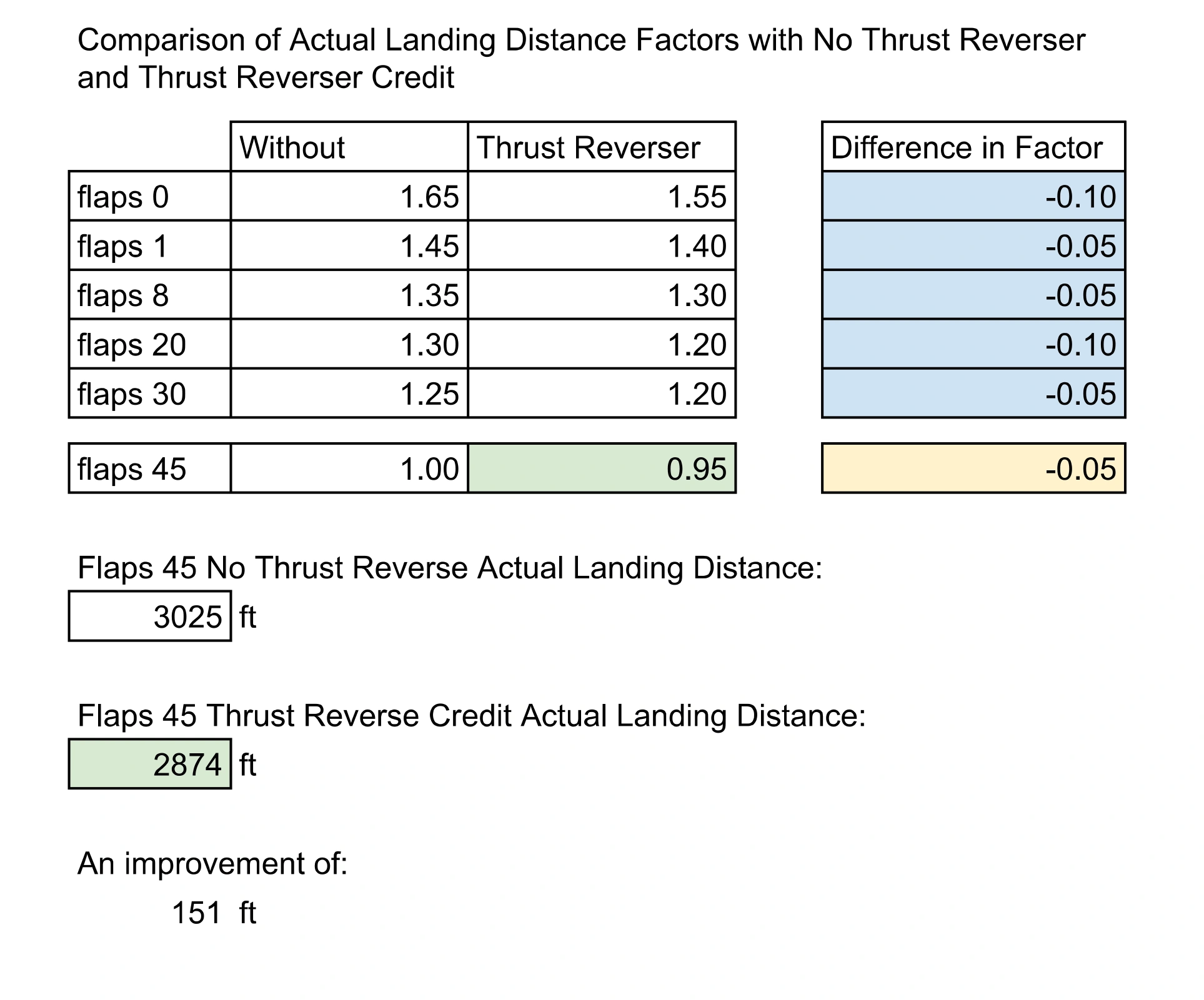

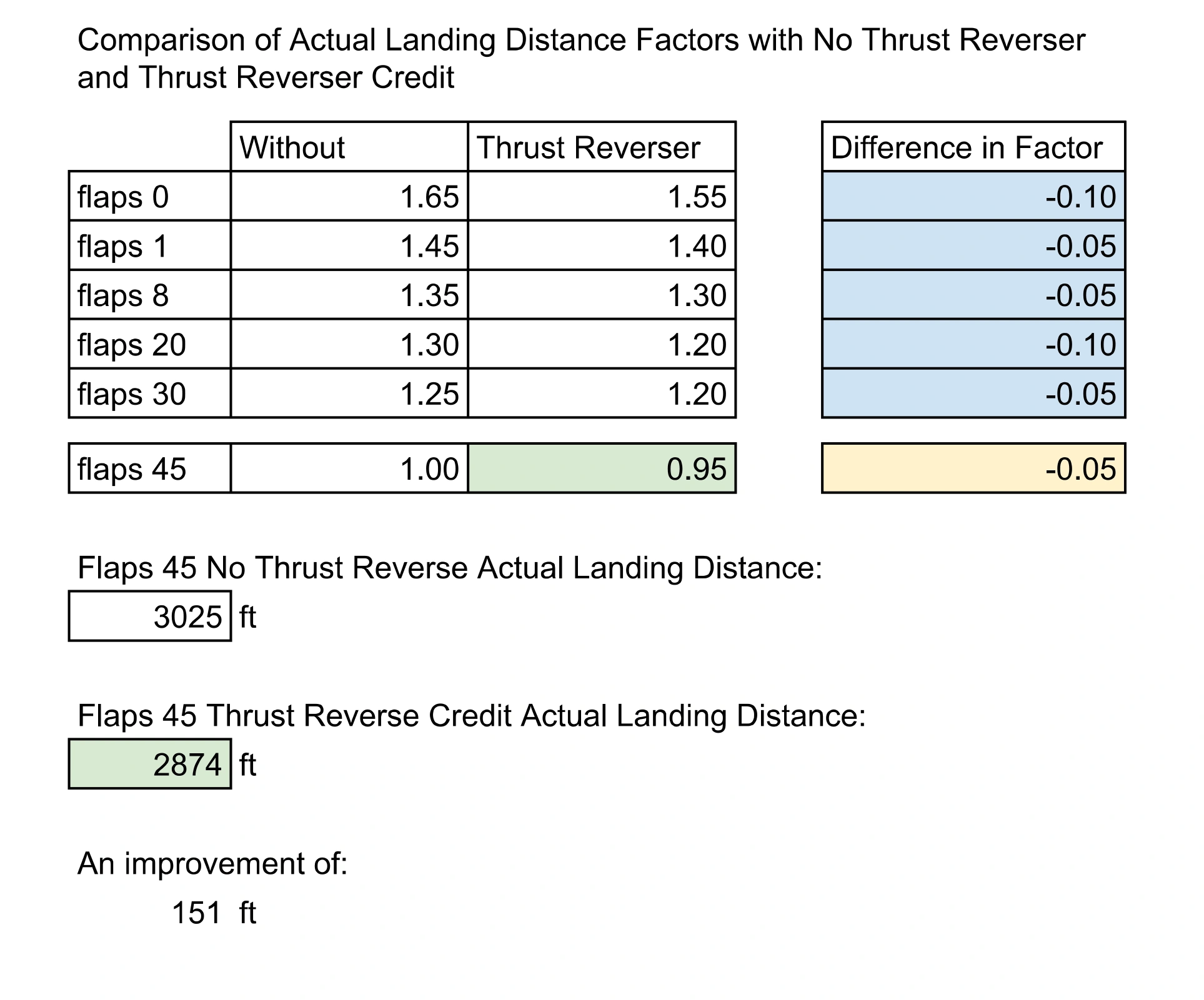

I couldn't help myself and did some math anyways to best estimate the effect of thrust reverse on a dry runway. The values in white are directly from QRH Vol. 1, I found a handy table that compared thrust reverse and no thrust reverser credit for all flap settings except flaps 45. I created a column in blue that compares the difference.

The difference is either -0.05 or -0.10. Since thrust reverse applies a force over time, and a flaps 45 landing should be slower and therefore take a shorter amount of time, I just selected -0.05 (in yellow) as the difference in thrust reverser credit for flaps 45.

Therefore we will consider the full thrust reverse dry runway landing to be 95% the length without thrust reverse. I compare the actual landing distance at a MGLW of 67,000lbs for a CRJ700 with (my estimate) and without thrust reverse.

The improvement is 151ft or the length of 1.42 CRJ700s. Is full thrust reverse on a dry runway marginal? It depends on the how assertive you brake.

From AC 25-32:

"Part 25 landing distances are determined in a way that represents the maximum performance capability of the airplane, which may not be representative of normal operations"

From the landing technique described in the FCOM, and in accordance with the regulations, the aircraft will cross the threshold at 50' and Vref, touchdown 1000' down the runway at some speed less than Vref=135kts but faster than Vsr=107kts, lets just say 125kts, lower the nose quickly, and apply maximum braking effort. The anti-skid will handle the rest.

Let's analyze this event in terms of time. Time for math. I will be converting everything to SI units first, then back again.

$$V_{\text{td}}(\text{kts})=125\text{kts}$$ $$V_{\text{td}}\left(\tfrac{m}{s}\right)=125\tfrac{\text{NM}}{\text{hr}}\cdot1852\tfrac{m}{\text{NM}}\cdot\frac{1\text{hr}}{3600\text{sec}}=64.31\tfrac{m}{s}$$ Where \(V_{\text{td}}\) is the velocity at touchdown.

The rollout distance can be determined as: $$d_{\text{roll}}(\text{ft})=\text{Actual Landing Distance}-1000\text{ft}$$ $$=3025\text{ft}-1000\text{ft}=2025\text{ft}$$ $$d_{\text{roll}}(m)=2025\text{ft}\cdot\frac{0.305m}{1\text{ft}}=618m$$

We will assume that the deceleration during landing is constant. I believe this is accurate, it would be uncomfortable if the force against the shoulder straps increased or decreased significantly during rollout. Our equation for velocity as a function of time is as follows:

$$v(t)=v_{\text{td}}+a\cdot t$$

$$v(t_{f})=v_{\text{td}}+a\cdot t_f=0\tfrac{m}{s}$$

where \(a\) is acceleration (it will be negative in our case),

\(t\) is time,

and \(t_{f}\) represents the time at which the aircraft reaches a complete stop.

We know how long the rollout is in terms of distance, but we must determine it in terms of time. We will use an integral. $$d_\text{roll}=\int_{0}^{t_f} v(t)\,dt=\int_{0}^{t_f} v_{\text{td}}+a\cdot t\,dt$$ $$=\left(a\cdot \frac{(t_f)^2}{2}+v_{\text{td}}\cdot t_f\right)-\left(a\cdot \frac{(0)^2}{2}+v_{\text{td}}\cdot 0\right)$$ $$=a\cdot \frac{(t_f)^2}{2}+v_{\text{td}}\cdot t_f$$

From our function of velocity versus time above, \(a\) can be related to \(t_f\) as follows: $$a=\frac{-v_{\text{td}}}{t_f}$$

Plugging this into our integral: $$d_\text{roll}=\frac{-v_{\text{td}}}{t_f}\cdot \frac{(t_f)^2}{2}+v_{\text{td}}\cdot t_f$$ $$=\frac{-v_{\text{td}}\cdot t_f}{2}+v_{\text{td}}\cdot t_f$$ $$=0.5\cdot v_{\text{td}} \cdot t_f$$

Solving for \(t_f\): $$t_f=2\frac{d_\text{roll}}{v_\text{td}}=2\frac{618m}{64.31\tfrac{m}{s}}=19.22s$$

A max performance landing rollout will last 19 seconds from touchdown to a complete stop.

Determining acceleration: $$a=\frac{-64.31\tfrac{m}{s}}{19.22s}=-3.3\tfrac{m}{s^2}$$

Before touchdown, the throttles are brought to idle. In the CRJ700, this is an increased landing idle, but in the CRJ200 it's just idle. Upon touchdown, both wheels must register WOW or wheel speed >20kts before thrust reversers can be deployed. Then, the engines must spool up. At 90kts, the thrust reversers begin to be stowed so that they are idle by 60kts.

On the CRJ200 reverse thrust can take up to 7 seconds to spool up. Landing idle and FADEC on the CRJ700 allows it to spool faster, but it still isn't instantaneous, it might take around 2-3 seconds.

From our equation for velocity as a function of time, let's see how long it takes to slow from touchdown to 90kts. $$v(t)=v_{\text{td}}+a\cdot t$$ Solving for \(t\): $$t=\frac{v(t)-v_{td}}{a}$$

Convert 90kts to \(\tfrac{m}{s}\): $$90\tfrac{\text{NM}}{\text{hr}}\cdot1852\tfrac{m}{\text{NM}}\cdot\frac{1\text{hr}}{3600\text{sec}}=46.3\tfrac{m}{s}$$ Determining time to slow from Vref to 90kts: $$t=\frac{46.3\tfrac{m}{s}-v_{\text{td}}}{a}=\frac{46.3\tfrac{m}{s}-64.31\tfrac{m}{s}}{-3.3\tfrac{m}{s^2}}=5.5s$$

And right here is the answer. Why does reverse thrust hardly matter on a maximum effort, dry, flaps 45 landing? Because the brakes are so effective, the thrust reverser hardly has the opportunity to even spool up before being idled again.

During a normal landing, idle or full reverse thrust is used until 90kts when reversers begin to be stowed and wheel braking gradually applied. The acceleration is still mostly constant.

Let's do some comparisons to the numbers above using a 5000' roll out.

5000' to meters: $$5000\text{ft}\cdot\frac{0.305m}{1\text{ft}}=1525m$$

The amount of time the rollout lasts: $$t_f=2\frac{1525m}{64.31\tfrac{m}{s}}=47s$$

The acceleration: $$a=\frac{-64.31\tfrac{m}{s}}{47s}=-1.4\tfrac{m}{s^2}$$

The amount of time from touchdown to 90kts: $$t=\frac{46.3\tfrac{m}{s}-v_{\text{td}}}{a}=\frac{46.3\tfrac{m}{s}-64.31\tfrac{m}{s}}{-1.4\tfrac{m}{s^2}}=12.9s$$

13 seconds is plenty of time for the thrust reversers to make an impact.

From Operational Advantages of Carbon Brakes, "steel brake wear is directly proportional to the kinetic energy absorbed by the brakes". Kinetic energy is proportional to the square of the velocity, so the slowest speed brakes can be applied the better for brake wear.

The equation for kinetic energy is: $$KE=\frac{mv^2}{2}$$

The weight of the aircraft converted to kg: $$67,000\text{ lbs}\cdot0.45\tfrac{\text{kg}}{\text{lb}}=30140\text{ kg}$$

The kinetic energy upon touchdown: $$KE=\frac{30140\text{ kg}\cdot(64.31\tfrac{m}{s})^2}{2}=6.2\times10^7\text{ joules}$$ Applying the brakes at touchdown would convert all of that energy into heat in the wheel brakes. (Ignoring drag, axle friction, etc...)

The kinetic energy remaining at 90kts: $$KE=\frac{30140\text{ kg}\cdot(46.3\tfrac{m}{s})^2}{2}=3.2\times10^7\text{ joules}$$ Delaying brake application until around 90kts reduces the amount of energy absorbed by the wheel brakes by half. If energy absorption is directly proportional to brake wear, delaying brakes until 90kts cuts brake wear in half.

Another consideration is brake temperature at the beginning of the next flight. Heavy brake usage could require an extended cooling period before another takeoff could be performed.

My company has an idle reverse thrust landing initiative. In ideal conditions and runways longer than 7,500', they ask us to use idle reverse thrust whenever possible.

This indicates they prefer conserving fuel and engine wear in exchange for increased brake wear.