When an aircraft brakes, kinetic energy of movement is converted into heat energy in the brakes. Taxiing increases the brake temperature. Landings are a high energy event, but the brakes had an opportunity to cool during the flight. Taking the runway for take off however, we must ensure that the brake temperatures aren't still too hot from taxi and the inbound landing an hour prior. The possibility of a high speed rejected takeoff will require the maximum energy consumption by the brakes of any operation. The hotter the brakes are to start with, the less margin for energy absorption is available.

From the PRM:

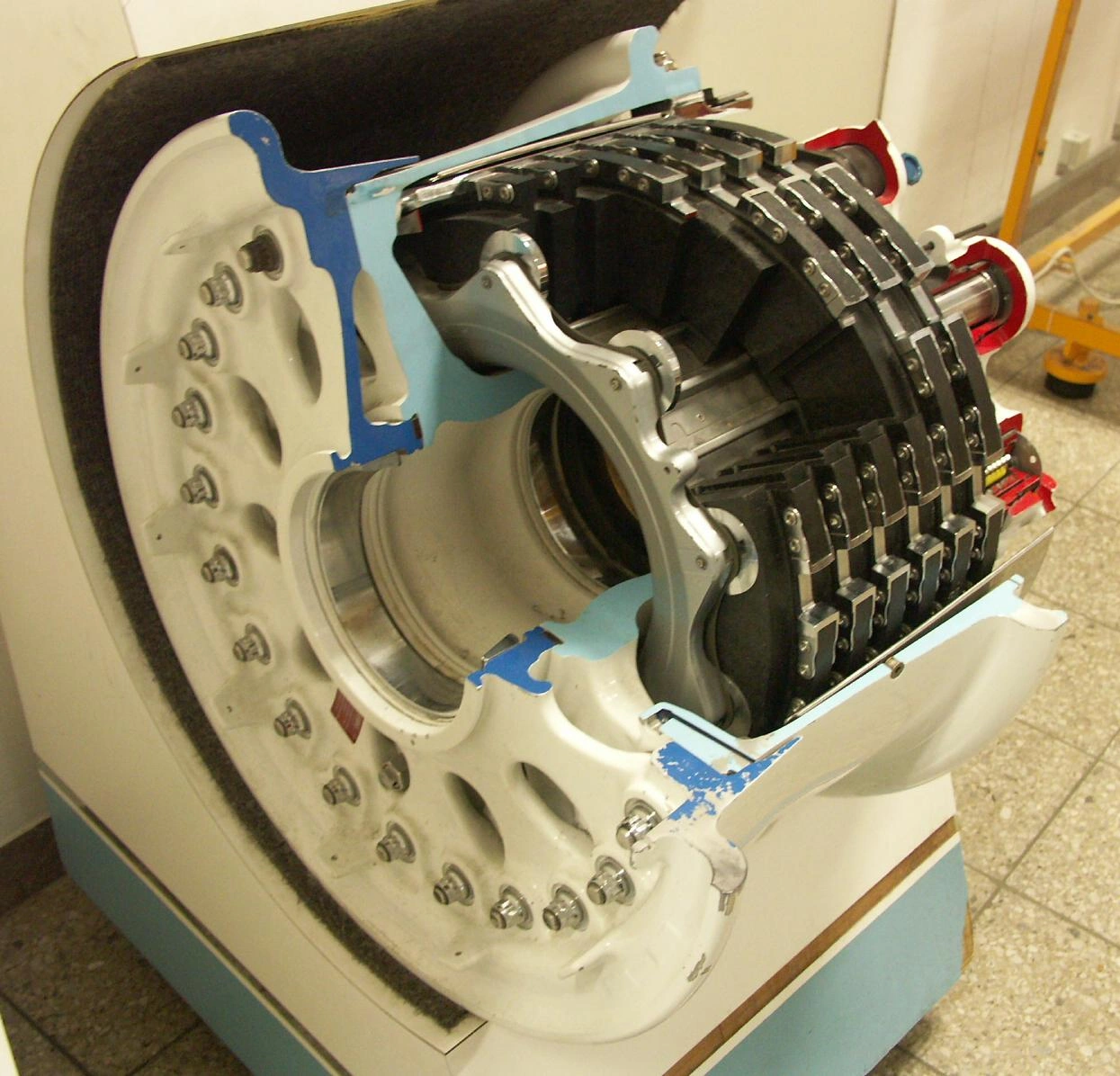

The braking system on the CRJ700 uses multi-disc steel brakes on each of the four wheels of the main landing gear.

The Brake Temperature Monitoring System (BTMS) consists of a temperature probe for each of the four brakes. There is a numerical readout in the bottom right side of second EICAS display.

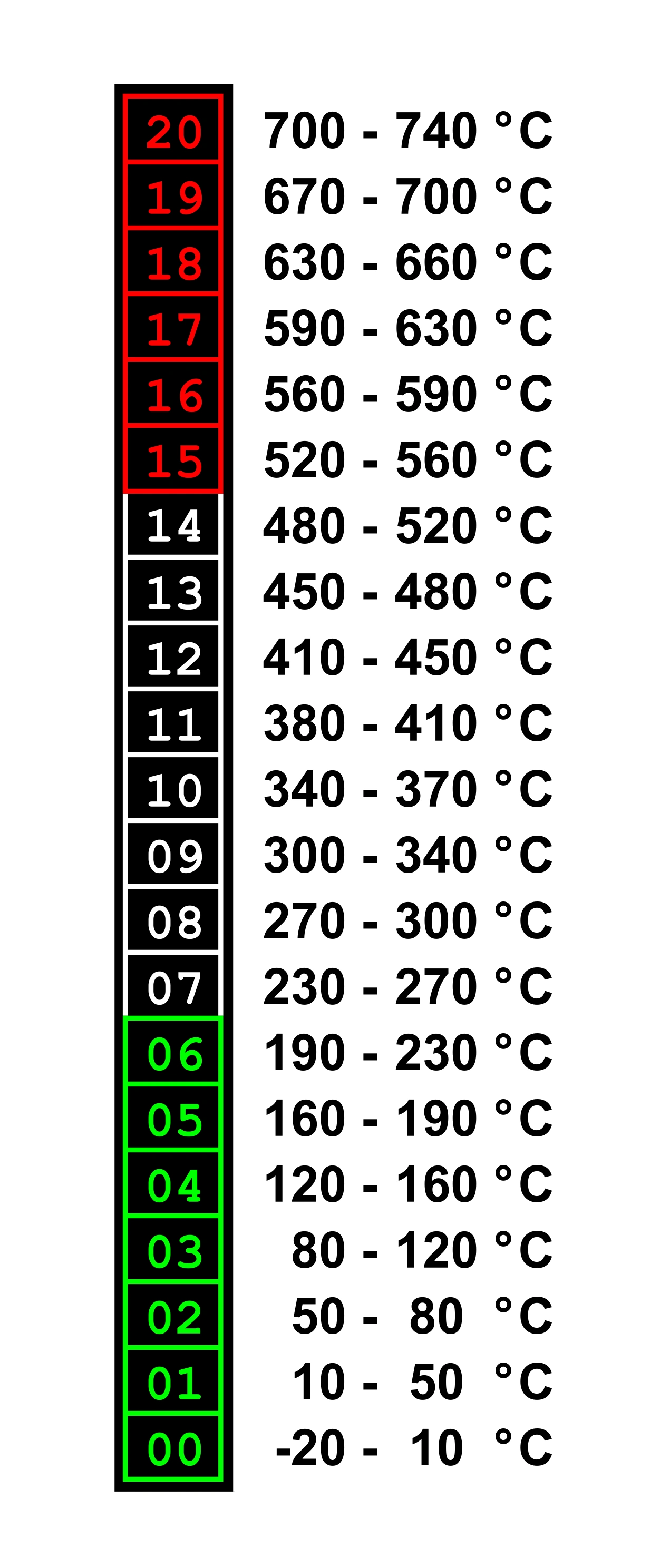

The values range from 00 to 20, and increases in increments of about 35°C.

From the FCOM Vol. 1:

00-06 is color coded green, 07-14 white, and 14-20 red, indicating an overheat. A reading of six indicates ≤ 220°C and 14 indicates ≤ 492°C.

Based the information from the PRM and FCOM, here is my table of estimated temperature values per BTMS value. The math does not work out perfectly, so I rounded to the nearest 10.

For reference, steel melts around 1500°C (https://www.americanelements.com/meltingpoint.html). Aircraft tires are constructed of rubber which melts at 260° and synthetic fibers which melt at 900°C (https://interestingengineering.com/videos/the-engineering-behind-the-small-but-mighty-airplane-tires).

I don't know what the fusible plug temperature is for my aircraft's wheels, but this manufacturer produces aviation fusible plugs in the range of 140°C to 220°C. (https://precisionaero.com/fusible-plugs/)

The brakes are also densely sandwiched and located inside the wheel.

From the AFM:

After landing or rejected takeoff, 15 minutes must be observed and indications must be green before another takeoff. Temperature indications are not instantaneous. It might take 15 minutes for the heat to 'soak' through the brake and wheel assembly and reach the temperature probe.

Case Study: Falcon CS-DFE

This crew conducted 8 accelerate-stop test runs over the course of 18 minutes until the fusible plugs on their tires melted.

If an overheat warning is displayed, the fusible wheel plugs must be inspected.

This past week, I paid attention to brake temperatures following my landings. I usually began brake application around 90kts and was flying a 60,000lb aircraft.

I observed brake temperatures range from 03-04 within 15 minutes; temperatures of 100-150°C.

The forces involved in stopping were primarily the brakes, however there is also idle reverse thrust, drag, and wheel axle friction to at work. I am going to consider these effects negligible and assume that all the energy of motion was converted into heat in the brakes.

Kinetic energy can be expressed as:

$$\text{KE}=\frac{mV^2}{2}$$

where \(\text{KE}\) is kinetic energy in joules (\(J\)),

\(m\) is the mass in kilograms,

and \(V\) is the velocity in meters per second (\(ms^{-1}\)).

Converting to SI units: $$90\text{kts}=46.3ms^{-1}$$ $$60,000\text{lbs}=2.7\times10^4kg$$

Calculating the energy absorbed by the wheel brakes: $$\text{KE}=\frac{(2.7\times10^4kg)(46.3ms^{-1})^2}{2}=2.89\times10^7J$$

Heat energy can be expressed via the following relationship:

$$q=mC\Delta T$$

where \(q\) is thermal energy in joules,

\(m\) is the mass of the substance in kilograms,

\(C\) is the specific heat capacity of a material in units of joules per kilogram Kelvin (\(Jkg^{-1}K^{-1}\)),

and \(\Delta T\) is the change in temperature of a substance in units of Kelvin (\(K\)).

The wheel brakes are steel, and steel has a specific heat capacity of about 500 \(Jkg^{-1}K^{-1}\). (https://www.engineersedge.com/materials/specific_heat_capacity_of_metals_13259.htm)

Let's assume the brakes start at a temperature of 0°C and increase to a temperature of 150°C based on my observation of BTMS values of 3s and 4s. That's a change of 150° in both Celsius and Kelvin.

We now have all we need to take a stab at guessing the mass of the aircraft's brakes.

Solving the heat energy equation for mass: $$m=\frac{q}{C\Delta T}=\frac{2.89\times10^7J}{500Jkg^{-1}K^{-1}\times150^\circ K}=386\text{kg}$$ $$386\text{kg}=850\text{lbs}$$ $$\approx200\text{lbs per wheel}$$

Despite the crudeness of my anecdotal data collection, research on web forums leads me to believe that 200lbs per brake might actually be pretty close.

There is a very important point to be made here. The variables that go into brake temperature are simply mass and velocity.

We are ignoring the effects of drag and idle reverse thrust. Those forces would eventually stop the airplane, but it would be in excess of 12,000ft (take a look at the landing performance chart for an icy runway and no thrust reverse). The wheel brakes predominate.

It does not matter how long or how short your rollout is, it does not matter if you stand on the brakes or apply light pressure, the impact on brake temperature is almost the same. What matters is the aircraft weight, and the speed at which the brakes begin slowing the aircraft.

Now that we have estimated the mass of the brakes, we can perform some analysis

Let's start with a case where the aircraft is rolling at 30kts, and we want to brake to a stop.

First we will find the energy in the moving aircraft: $$30\text{kts}=15\tfrac{m}{s}$$ $$KE = \frac{(2.7\times10^4kg)(15ms^{-1})^2}{2}$$ $$=3.04 \times 10^6 J$$

Solving the thermal energy equation for temperature: $$\Delta T=\frac{q}{mC}$$ $$=\frac{3.04 \times 10^6 J}{386\text{kg} \cdot 500Jkg^{-1}K^{-1}}$$ $$=16^\circ K (\text{or }C)$$ A brake application from 30kts to a complete stop raises the temperature 16°C.

Lets's consider now with engines at idle. At idle the engines are producing thrust. They are producing enough thrust to accelerate the aircraft. We like to taxi single engine to save fuel, but even with one engine at idle, a light CRJ700 will still accelerate. My operator does not permit the use of idle thrust reverse to null taxi thrust although most high mounted engine operators do.

The CRJ700 has two engines rated at a max thrust of 13,790 pounds of force which is equivalent to 61kN (kilo Newtons). The manufacturer does not publish idle thrust, so I have once again resorted to browsing the un-citeable web forums. Idle thrust being 5% of max thrust is what I am going to go with here.

To get energy (J) from a force, the thrust, we need to multiply force × distance. My best guess at how early I would start braking for a gentle stop from 30kts would be about 200 meters. That's 600 feet or two thirds the distance along a runway from the beginning to the aim point markers.

Therefore the brakes must absorb the energy from the mass of airplane moving at 30kts as calculated earlier in addition to the thrust of the engines during the braking event.

The work (energy) produced by 2 idling engines while braking over a 200m distance: $$\text{Work} = \text{Force} \cdot \text{Distance}$$ $$=(2\times 0.05\cdot61,000 N) \cdot 200m$$ $$=1.2\times10^6J$$

Adding this to our stopping energy from earlier: $$\Delta T=\frac{3.04 \times 10^6 J+1.2\times10^6J}{386\text{kg} \cdot 500Jkg^{-1}K^{-1}}$$ $$=22^\circ K (\text{or }C)$$ Running the math for a single engine taxi yields 19°C increase in brake temperatures.

Now 15-22°C may not sound like a lot, but just two brake applications is enough to increase the BTMS by one value.

The energy from the engines is dependent on distance too so stopping in a shorter distance would cause the increase in temperature to be closer to the 15°C value.

Due to the idle thrust of two and even just one engine, brakes must be used during taxi. There are two techniques, you can ride the brakes, or you can allow the aircraft to accelerate, then brake to a slower speed, and repeat the cycle.

Riding the brakes at a steady speed means the energy absorbed by the brakes is exactly the same as the energy output by the engine (ignoring other friction).

For aircraft with carbon brakes, the recommended taxi technique is to allow speed to build from 10kts to 30kts at idle, then brake back to 10kts and repeat. Aircraft Braking Systems Corp calls this technique 'snubbing' (source). Snubbing means the brakes absorb the kinetic energy of the aircraft slowing from 30 to 10kts, which must occur at periodic intervals during the taxi. (Carbon brakes wear less at higher temperatures).

Some captains at my operator are taught to use the snubbing technique and to avoid the brake riding technique. Why? I am not sure. Asking different captains yields unconfident answers, but something along the lines of riding the brakes causes them to be hotter. Is this true? Let's do some math and find out.

To recap, the change in temperature of the brakes can be expressed as: $$\Delta T=\frac{\Delta\text{KE}+(\text{force of 2 idling engines}\times\text{distance of braking event})}{\text{mass of wheel brakes}\times \text{specific heat of steel}}$$

Riding

Because riding the brakes is performed at a constant velocity, the change in kinetic energy is 0. The distance of the braking event is the distance of the taxi (excluding the beginning and end of taxi). $$\Delta T_\text{riding}=\frac{f_\text{engines}\cdot d_\text{taxi}}{m_\text{brakes}\cdot C}$$

Snubbing

For snubbing the change in kinetic energy is the change from our maximum taxi speed back down to our minimum taxi speed plus the force of engines over the braking event. The technique advises cycling between 30kts and 10kts, but I will leave them as a variables. $$\Delta T_\text{snubbing}=\frac{\frac{m_\text{aircraft}}{2}(v_\text{max}^2-v_\text{min}^2)+(f_\text{engines}\cdot d_\text{brake application})}{m_\text{brakes}\cdot C}$$

Comparison

Lets determine how much distance one of these cycles takes. The total distance will be distance for acceleration from the minimum speed to maximum speed, plus the distance for the braking event: $$d_\text{total}=d_\text{accel}+d_\text{brake application}$$

From \(F=m\cdot a\): $$a = \frac{f_\text{engines}}{m_\text{aircraft}}$$

Creating a function of velocity versus time with the aircraft starting at minimum taxi speed at time=0: $$v = \frac{f_\text{engines}}{m_\text{aircraft}}\cdot t + v_\text{min}$$

We will skip the integral math today, the distance traveled during acceleration is expressed as: $$d_{accel} = \frac{1}{2}\frac{f_\text{engines}}{m_\text{aircraft}}\cdot t_\text{max speed}^2 + v_\text{min} \cdot t_\text{max speed}$$

The amount of time it takes to reach maximum taxi speed: $$v_\text{max} = \frac{f_\text{engines}}{m_\text{aircraft}}\cdot t_\text{max speed} + v_\text{min}$$ $$t_\text{max speed}=(v_\text{max}-v_\text{min}) \frac{m_\text{aircraft}}{f_\text{engines}}$$

Putting it together to determine the distance: $$d_\text{accel} = \frac{1}{2}\frac{f_\text{engines}}{m_\text{aircraft}}\cdot \left((v_\text{max}-v_\text{min}) \frac{m_\text{aircraft}}{f_\text{engines}}\right)^2 + v_\text{min} \cdot \left((v_\text{max}-v_\text{min}) \frac{m_\text{aircraft}}{f_\text{engines}}\right)$$ which simplifies to: $$d_\text{accel}=\frac{m_\text{aircraft}}{2f_\text{eng}}(v_\text{max}^2-v_\text{min}^2)$$

Going back to our equation for riding the brakes, lets look at riding the brakes for the distance of one cycle of snubbing: $$\Delta T_\text{riding}=\frac{f_\text{engines}\cdot (d_\text{accel}+d_\text{brake application})}{m_\text{brakes}\cdot C}$$ $$=\frac{f_\text{engines}\cdot d_\text{accel}+f_\text{engines}\cdot d_\text{brake application}}{m_\text{brakes}\cdot C}$$ $$=\frac{f_\text{engines} \left(\frac{m_\text{aircraft}}{2f_\text{eng}}(v_\text{max}^2-v_\text{min}^2)\right) +f_\text{engines}\cdot d_\text{brake application}}{m_\text{brakes}\cdot C}$$ $$=\frac{\frac{m_\text{aircraft}}{2}(v_\text{max}^2-v_\text{min}^2) +f_\text{engines}\cdot d_\text{brake application}}{m_\text{brakes}\cdot C}$$ And this equation is exactly the same as our \( \Delta T_\text{snubbing} \) equation.

I did this in generic variables so it doesn't matter if my estimates of brake mass or idle thrust output are correct. What matters is the mathematical relationship of the variables involved, and it appears the brake riding and snubbing techniques incure identical penalties on brake temperature.